When Islamic State fighters conquered the border region between Iraq and Syria, the Yazidi village of Kocho also fell into their hands. Twenty-year-old Nadia was among dozens of young women who were abducted and abused. This is the story of her capture and escape.

Nadia Murad Basee Taha, a young Iraqi Yezidi who was abducted into slavery by members of ISIS, is photographed in the U.S. (Image: Kirsten Luce/TIME).

Nadia Murad Basee Taha, a young Iraqi Yezidi who was abducted into slavery by members of ISIS, is photographed in the U.S. (Image: Kirsten Luce/TIME).

Twenty-one-year-old Nadia Murad Basee Taha traveled to New York City to testify in front of the U.N. Security Council on December 16, about the plight of the Yezidi ethnic and religious minority under ISIS.

“I cannot imagine how painful it must be every time you are asked to recount your experience,” U.S. Ambassador to the U.N. Samantha Power said to Nadia after her testimony on Wednesday. “And your being here and speaking so bravely to all of us is a testament to your resilience and your dignity — and it’s of course the most powerful rejection of what ISIL stands for.”

Nadia was in New York City to ask the U.N. Security Council to rescue the enslaved Yezidis and help them liberate their land from the militants. She was also there to tell her story, with the help of Yazda, a U.S.-based nonprofit dedicated to supporting survivors of Yezidi genocide and women who have escaped from ISIS.

1. LIFE BEFORE ISIS ARRIVED

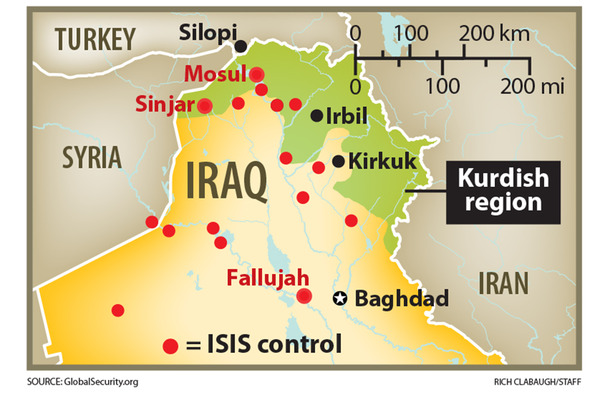

Nadia was born and raised in the Kurdish region of Syria by her mother Shama and father Murad. Her hometown of Kocho, which once boasted a population of 1,700, lies near the Sinjar Mountains not far from the border between Iraq and Syria. Their home is located not far from the Iraqi Kurdish city of Dohuk, on the “safe” side of the front.

Nadia’s life in Kocho village with her mother, brothers, and sisters was a simple one. She was a student, and history was her favorite subject. She dreamed of going to college someday, perhaps even becoming a teacher and buying an apartment of her own, with shelves filled with books.

Her family was not rich, but they were able to make ends meet. They had around 50 sheep, two dozen chickens and a few goats. Nadia’s older brothers worked as day laborers while her mother sold milk, yogurt, eggs and cheese. Sometimes even Muslims from the neighboring towns came to make purchases.

Some households in the village, including hers, had a TV and Nadia’s favorite broadcasts were music shows and horror movies, as long as the good guys won in the end. She even saw a World Cup soccer match, Germany versus Brazil. But she “did not know anything,” she says of her generally peaceful childhood. “I did not know anything about what ISIS was or what it was going to do.”

But soon she began to see images on TV, “horrific images,” she says. And one day in August, she was walking with her sister and saw fighters in her village. “I recognized, I said, ‘This is the same group that we have seen committing the crimes on the TV.’” She didn’t know she would meet them so soon.

2. LEFT UNPROTECTED

In the summer of 2014, Kurdish fighters in the border region of northern Syria and northern Iraq retreated before the rapid advance of IS troops. The fighters of the “caliphate,” superbly armed and well-organized, seized control of large areas. More than 1.8 million people have fled the region, according to a United Nations report. From January to the end of September, approximately 17,386 civilians were wounded and 9,347 killed. In addition, Kurdish military officials estimate that thousands of young women were abducted.

ISIS has targeted the Yezidi population of approximately 230,000 people in the area, considered “kafir” or “nonbelievers” because they do not practice Islam, in what is widely considered to be a genocide. Over 5,200 Yezidis were abducted in 2014 and at least 3,400 are still in ISIS captivity, according to community leaders, and most, if not all, of the captives are women (male captives are indoctrinated and forced to fight, or risk execution). Thousands more have been slaughtered, and over 400,000 Yezidis have been forced from their homes.

Even worse, ISIS has revived the institutional practice of slavery within its so-called caliphate, condoning the systematic rape and sexual enslavement of non-Muslim women. This practice is not only allowed inside ISIS, it is actively encouraged, and some survivors have reported that ISIS fighters believe that if a woman is raped by 10 Muslims, she will become converted. There is even a market for enslaved women within the caliphate, and girls are bought, sold, and traded among the fighters as commodities or rewards.

Amid all this turmoil, Nadia’s town was suddenly left unprotected.

3. ISIS INVADES, THE CAMPAIGN OF TERROR BEGINS

Islamic State fighters came to Nadia’s town several times July 2014, always at intervals of one or two days. They took great pains to demonstrate their military strength, roaring into town and announcing that they were the new lords of the land. The men wore mirrored sunglasses, kept their faces masked with black scarves, and carried pistols and daggers in their belts, recalls Nadia.

At first, they led the townspeople to believe that they were safe, as long as they handed over their weapons, mostly old hunting rifles and kitchen knives. They told the men of Kocho that disarmament was the price to pay they had to pay to avoid being killed by Islamic State fighters.

Then, on Aug. 15, 2014, after all the weapons were collected and piled up on the back of a pickup truck, the fighters told everyone to walk to the school on the outskirts of town. It was lunchtime. On their way, Nadia and her family saw ISIS fighters “everywhere,” she remembers, “on the houses, on the streets, there were a lot of them.” Some of them were masked, others were not. They all spoke different languages.

The fighters separated the men from the women, and put Nadia and some other women on the second floor of the building. At the last moment, her mother slipped a gold ring from her finger and gave it to Nadia: “In case you need it,” she whispered. This is Nadia’s last memory of her mother.

ISIS fighters murdered 312 men in one hour, according to a U.N. spokesman, including six of Nadia’s brothers and stepbrothers. Nadia witnessed it all.

When they retook the area from ISIS, Kurdish forces also uncovered a mass grave of about 80 elderly women who had presumably been executed because they were too old and undesirable to be sold into slavery.

Those who remained, the women like Nadia who were considered young and attractive, were taken to the occupied Iraqi city of Mosul, where they stayed for three days before they were “distributed” among the fighters to be enslaved. “They gave us to them,” Nadia says.

4. SEXUAL ENSLAVEMENT: ISIS ACCESS TO WOMEN AND MONEY

Every morning in Mosul, the women would be required to wash. Nadia recalls some women mussing up their hair to look less appealing to the fighters, in hopes they would be spared. Others smeared battery acid on their faces. “It did not help because in the mornings they would ask us again to wash our face and look pretty.”

Then, Nadia says, they would be taken to the Shari‘a court, where they would be photographed. The photographs would be posted on a wall in the court, along with the phone number of whichever militant or commander currently owned each woman, so that fighters could swap women among themselves.

Nadia’s niece, who was also kidnapped, witnessed a woman cutting her wrists. They heard stories of women jumping from bridges. And in one house in Mosul where Nadia was kept, an upstairs room was smeared with evidence of suffering. “There was blood and there were fingerprints of hands with the blood on the walls,” she says. Two women had killed themselves there.

Nadia says the women debated whether they could attack one of the men and kill him. But there was a constant coming and going, with new men arriving all the time, carrying weapons and clad in black or khaki fantasy uniforms, and then the fighters would withdraw for long discussions. “They always came in groups of three or four. And they were always armed. At one point we broke a window pane, and each of us women hid a shard of glass up our sleeves, so we could kill ourselves if we couldn’t take it anymore.”

Nadia never considered ending her own life, but she said she wished the militants would do it for her. “I did not want to kill myself — but I wanted them to kill me.”

One of them tore her mother’s gold ring from her finger and slipped it onto his own hand. Nadia swore: I will find this man one day, and I will cut off his finger, and I will take back my ring.

This man was probably a local, says Nadia, who notes that he spoke no Arabic, but rather the Kurdish dialect that is commonly used in her region. She says that there were two groups of IS fighters: men who appeared to be highly devout, who were leaders of a sort, and who spoke Arabic — and men who spoke a mixture of Arabic and Kurdish, whose devotion seemed rather feigned, and whose accent divulged that they came from the border region. These were apparently fighters who had joined the presumed victors to gain access to money and women.

5. NINE DAYS OF HELL

Nine days can be longer than an entire lifetime, says Nadia, and she can remember every second of those nine days.

ISIS frequently moved the women from one house to another. There seemed to be no rhyme or reason for the frequent moves; they were apparently dependent on the whims of their captors. The first house, Nadia recalls, belonged to a judge named Ghasi Hussein, who had fled the area, one of their captors told the young women. But in the future, as the man said, it will belong to them, in honor of Allah. Photos of the judge and his wife still hung on the walls, and he had had teacups printed with their likeness. The men and their prisoners stayed there for three days before they moved to a second, a third, a fourth and a fifth house.

Sometimes they were given nothing to eat, other times just a putrid egg for six young women. For two long days, they received no water. It was extremely hot and their captors had given them a single glass of tea. They passed around the glass — two tiny sips for each woman. If you convert to Islam, the men said, you’ll be given as much fresh water as you want.

“We remained steadfast,” says Nadia.

On another occasion, they were deprived of drinking water once again, only this time their captors put down a bucket of used bathwater. It tasted like soap and reeked of urine, but they had nothing else.

Their captors beat them, sometimes several times in a single day, for no apparent reason. There was a man with a beard who used an electric cable, while two others preferred wooden switches. Sometimes they were also punched and kicked, and they were repeatedly sexually abused.

6. NADIA’S TURN

One day, it was her turn. She was sitting in a room with all the other women, looking down. She was wearing a pink jacket. A fighter came in. “He told me, ‘The woman in the pink jacket, stand up for me,’” Nadia says. “When I raised my head I looked at him, this huge man, and I shouted and screamed.” He was very big, she says, with long hair and a long beard. She was sitting with her three nieces, they all held on to each other as the big man tried to drag her from the group. “They were beating us with sticks while we were holding one another,” she says. “He took me by force to the ground floor, and they were writing the names of those they were taking.”

As she was struggling with the big man, she saw a pair of small feet. It was another ISIS fighter, also there to get a Yezidi slave. Nadia, desperate, wanted to go with him because he had a smaller build than the first man. “I basically jumped on his feet, and I told him, I begged him, ‘Free me from this huge person, take me for yourself and I will do whatever you want,’” she says. “Then he took me for himself.”

Nadia’s new captor was tall and thin, with long hair but a trimmed beard, and an “ugly mouth” with “teeth coming out of his lips.” This new man kept Nadia in a room with two doors. He prayed five times a day. He had a wife and a daughter named Sara, but Nadia never met them. One day he took her to his parents’ house in Mosul. “Then he one day forced me to dress for him and put make-up, I did, and in that black night, he did it,” she testified.

She told the hushed room that she tried to escape the rape and torture, but was captured. “That night, he beat me up, forced to undress, and put me in a room with six militants,” she said in her testimony.

Nadia doesn’t give a literal account of these rapes. It is virtually impossible for her to talk about them, and it contravenes the conventions of her culture.

She merely says: “They continued to commit crimes to my body until I became unconscious.” Then she lowers her head, in silence, awash with shame.

“What else could we do?” she says after a while, now speaking very quietly.

She says the men were merciless. Some women threw themselves at their tormentors’ feet, kissed their knees and hands, and — her eyes filled with tears — pleaded for mercy. It was no use. The men remained unmoved and did not exhibit an ounce of regret for their behavior. When one ISIS fighter was asked whether she was his wife, he announced, “‘This is not my wife, she is my sabia, she is my slave,’” Nadia recalls. “And then he fired shots in the sky, as a sign of happiness.”

7. ESCAPE FROM CALIPHATE CAPIVITY

Back on the first day, the men who kidnapped Nadia and the other young women as hostages and sex slaves had away taken their shoes. Escaping barefoot was out of the question. As the women could see from the windows, the surrounding terrain was rough and rocky, and they would end up with bleeding cuts and gashes all over their feet. But Nadia found found a pair of pink tennis shoes under some rags in one of the houses she stayed. Though they were a few sizes too small for her, she thought they might do.

Six men — her captors, rapists and tormentors — stood guard from day one. But on the ninth night, Nadia noticed that four of the men were apparently absent, perhaps sleeping elsewhere. Whatever the case, only two of the Islamic State fighters were sitting in the kitchen that night — and they were distracted. It looked as though they were arguing.

The men had shut up Nadia alone that night and she didn’t know where the other young women were. The lock on her door was defective and she was able to open it. She pulled out the tennis shoes that she had kept hidden, crammed her feet into them, slipped out of the room and was able to push open a terrace door. She scurried out of the house and rushed through the garden, filled with rustling dry bushes and trees. She was afraid that a dog would start barking, but she was lucky.

She came to a wall, a high wall, so it seemed — reaching beyond her outstretched arms. “Now I had to climb over the wall,” she says, “and I didn’t have much time.”

Nadia landed safely and started running, quietly, but as quickly as she could. “Don’t even think of running away!” the men yelled at her. They said she would be recaptured within an hour, saying they had announced a reward for $5,000 (€3,950) for fugitives. The punishment for attempted escape, the men added, was death.

It was pitch black on the other side of the wall. Far in the distance, she recalls, she could make out the dim, yellowish lights of a city. She was afraid to jump. But she did so anyway.

Nadia escaped her captivity in November 2014.

8. HOMESICK FREEDOM

After she jumped over the wall, Nadia ran toward the lights and managed to reach downtown Mosul, once a burgeoning metropolis of almost 2 million people, and the second largest city in Iraq after Baghdad. But as she walked through the streets, Mosul seemed empty and deserted.

From time to time, she ducked into building entrances and behind bushes, to keep an eye out for possible pursuers. Although she knew she was in Mosul, she was unfamiliar with the city. Finally she came to a residential area and, suffering from severe exhaustion, picked a door at random.

After she knocked persistently, a sleepy-eyed man opened the door and shined his mobile phone light in her face. Nadia cried as she told him who she was and what had happened to her. The man pulled Nadia into the house and fetched his wife. The two of them hid Nadia behind a pile of odds and ends in a room, gave her a mattress, a blanket and water. Nadia took off her shoes and discovered that her toes were bleeding.

She was subsequently transported to a refugee camp (she is purposely vague about how she got from captivity to the camp, perhaps to protect anyone who helped her), where she was selected for a program that takes refugees to Germany.

Now she’s living near Stuttgart, but she does not feel at home there. “I left everyone, all the family members who are still in the camps, I left them,” she says. “But it’s better than the poverty and suffering that people endure in the camps.” She’s been brought to the U.S. to raise awareness about the plight of Yezidi girls still in captivity.

Nadia does not celebrate Christmas, but she has learned about the holiday since she’s been living in Germany. And she has a message for anyone celebrating Christmas this year: “If they’re celebrating and they want to help the poor, then they should help us.”

Reprints & Sources: This blog post uses multiple sources to compose a more complete narrative of Nadia’s testimony, but the three primary sources are listed below.

Nine Days in the Caliphate: A Yazidi Woman’s Ordeal as an Islamic State Captive -By Ralf Hoppe | Der Spiegel (The original article appeared in German in Issue 42/2014, October 13, 2014.)

A Yezidi Woman Who Escaped ISIS Slavery Tells Her Story -By Charlotte Alter | TIME

Nadia Murad Basee Taha (ISIL victim) on Trafficking of Persons in Situations of Conflict | U.N. Security Council, 7585th Meeting (Official UN Testimony)