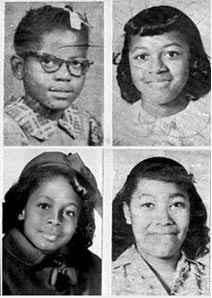

The four girls killed during the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing. Clockwise from top left: Addie Mae Collins (aged 14), Cynthia Wesley (aged 14), Carole Robertson (aged 14) and Denise McNair (aged 11)

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. — VICTIMS often absorb the shame that should belong to the perpetrators. For most of her 62 years, Sarah Collins Rudolph has confronted that misplaced emotion every time she looks in the mirror at a glass substitute for the eye she lost 50 years ago today, when members of the Ku Klux Klan bombed the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Ala. The same ambulance (colored) that took young Sarah to the hospital subsequently transported the corpse of her 14-year-old sister, Addie Mae Collins, who perished along with three other girls. The morning’s Sunday school lesson was on “The Love That Forgives.”

This anniversary year could have been an opportunity for Birmingham to practice some rigorous truth and painful reconciliation. It has ended up being a balkanized, largely ceremonial affair. The city’s Empowerment Week, an underpublicized festival of imported panelists and celebrities concluding today, exemplified the crux of the mission’s flaw: why is it so difficult to extend the notion of empowerment to include the powerless? We are more comfortable devoting civic resources to media events and monuments, like the life-size sculpture of the girls unveiled in Birmingham this week, than addressing the persistent casualties of the history being commemorated.

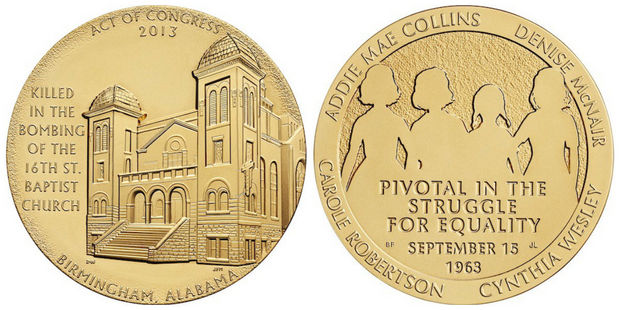

The sometimes impressive anniversary tributes stand in contrast to how little glory the bombing victims themselves caught over the years. Carole Robertson’s first name was misspelled on a marker at the church. Addie’s remains went missing from her grave. So when Congress awarded the girls its highest civilian honor, the Congressional Gold Medal, earlier this year, it was something of a shock that Ms. Rudolph responded, no thanks.

“I’m letting the world know, my sister didn’t die for freedom,” she told the press. “My sister died because they put a bomb in that church and they murdered her.” Declining to attend President Obama’s signing of the resolution in May, she stated her preference for compensation “in the millions.”

Ms. Rudolph did end up going to the formal medal ceremony at the Capitol on Tuesday. “What changed my mind is that I love my sister,” she explained to me. “She can’t talk for herself, but I can.” Also among the guests was the elderly father of another honoree, Denise McNair: Chris McNair, a once popular politician imprisoned on public corruption charges, had just been freed under new Justice Department guidelines for “compassionate release.” The Congressional leaders’ bipartisan homage to “the four little girls” could not overcome the unintentional theme of this anniversary year: half a century after the prime of the civil rights movement, why does so much of its promise remain unfulfilled, the sacrifice unrequited? The recent 50th anniversary celebrations of the March on Washington were mocked by the Supreme Court’s evisceration of the Voting Rights Act and the violent death of yet another black innocent, Trayvon Martin.

We are understandably drawn to cheaper correctives: posthumous pardons for the Scottsboro Boys in Alabama; plaques at the Birmingham city hall dedicated, in August, to Virgil Ware and Johnny Robinson, two other black children killed by whites on Sept. 15, 1963. If the structural changes achieved by these symbolic gestures are roughly none, their appeal is that they also cost nothing. To wit: the Congressional resolutions conferring the medal last spring passed unanimously.

The Congressional Gold Medal was posthumously presented to the families of the four girls killed in the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing on Tuesday, Sept 10, 2013.

Modern-day Americans seem loath to do the right thing unless it’s also the smart thing — even “compassionate release” has to be touted for its cost-saving virtues. Birmingham’s black-majority city government knew it had to sell the yearlong commemoration of 1963 as a big economic boon and named a co-chairwoman highly palatable to the business establishment, the native daughter Condoleezza Rice.

Likewise, when I spoke to the Birmingham Rotary Club a couple of years ago, I strategically stressed the practical benefits of a proposal I had been advocating: a fund that would offer a tangible “I’m sorry” to sufferers like Ms. Rudolph. Reminding the city elite of the relentless question they would be facing in 2013 — “How has Birmingham changed?” — I suggested that nothing would convince the world that they “got it” like cash.

As the Harvard law professor Charles J. Ogletree has written, even the most hostile critics of reparations for slavery raise little objection to payments for specific Jim Crow injustices — that is, “to identifiable victims where there is an identifiable harm,” as in the Tulsa race riot of 1921, for which the Oklahoma Legislature made limited restitution in 2001.

But despite the Birmingham Rotarians’ gratifying openness to a fund for victims (as well as heroes), follow-up discussions bogged down on how to define “eligibility.” My black advisers’ reservations reflected the continued friction between the activists who “shook the apple tree,” in the phrase of one civil rights leader, and those who stood on the sidelines and subsequently picked up the apples.

And the whites seemed to sense that our civic institutions were so criminally compromised by segregation as to render the eligibles virtually endless.

Read more: Civil Rights Justice on the Cheap -By Diane McWhorter | NYT

Long Forgotten, 16th Street Baptist Church Bombing Survivor Speaks Out –By Tanya Ott | NPR